By Julian De Ocampo ’13

THE ROUNDUP

In a New York Times blog post last November entitled “How to Live Without Irony,” Princeton professor Christy Wampole penned a stunning critique of contemporary culture’s ironic detachment, attributing much of this shift to the rise of social media.

“Our incapacity to deal with the things at hand is evident in our use of, and increasing reliance on, digital technology. Prioritizing what is remote over what is immediate, the virtual over the actual, we are absorbed in the public and private sphere by the little devices that take us elsewhere,” Wampole wrote.

But Wampole only scratches the surface when it comes to pinning down these social shifts. The Internet is fundamentally changing the way we act not only online, but offline as well.

And frankly, many of this shifts are concerning at the very least. It appears to paint an image where social interaction itself has become devalued.

While the merits of social media are numerous, there is no better time than the present to stop for a moment and reconsider the way we’re choosing to reshape our culture.

Flashes on the screen

In Gary Shytengart’s 2010 dystopian novel “Super Sad True Love Story,” little devices carried by civilians expose everyone’s life stories for the world to see.

People in bars stand around shyly scanning digital information for potential mates around them, instantly initiating their socialization based on compatibility ratings generated from economic statistics, interests, attractiveness and sexual history.

It would almost be funny if it didn’t cut so close to the bone.

The sheer amount of information available online on any given person has decreased the functional need to communicate meaningfully. Why have a conversation when you can just check a Twitter feed or Facebook wall?

And while some would point to pornography as a cause of objectification, the real target may be a little closer to home than that.

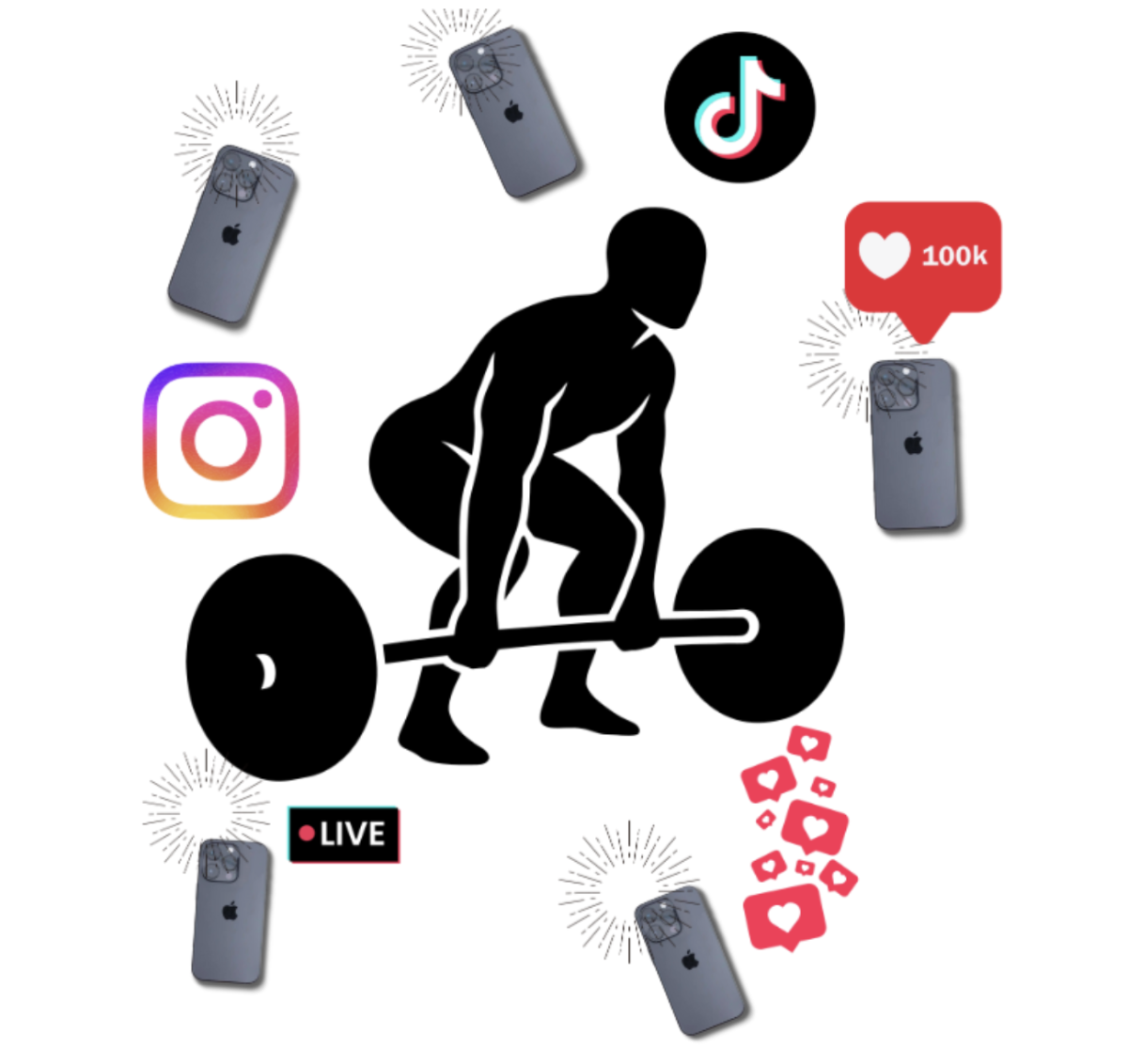

Facebook propagates this mentality by creating an environment where racy pictures are affirmed by hundreds of likes and comments and people offer tactless, shallow compliments to the anonymous images on their screens.

An attractive male or female now has the capability to become a minor celebrity within a community from the confines in their bathrooms, where mirror pictures flood the news stream.

Snapchat has turned photography into an exercise in this inconsequential way of thinking, where images last for five seconds and leave quick imprints in your mind before dissolving into oblivion.

When reputations can rise and fall based on status updates, we inevitably have to ask ourselves if that’s the type of hierarchy we want to create.

Streamlined courtship

A recent analytical article in The Atlantic by columnist and author Dan Slater entitled “A Million First Dates” characterized the modern dating scene as one that is quickly growing to value instant gratification while disregarding the merits of long-term monogamy, especially due to the rise of online dating sites.

“People are more likely to leave relationships, because they’re emboldened by the knowledge that it’s no longer as hard as it was to meet new people. But whether it’s dating sites, social media, e‑mail—it’s all related to the fact that the Internet has made it possible for people to communicate and connect, anywhere in the world, in ways that have never before been seen,” divorce attorney Gilbert Feibleman said in the article.

And while writers have responded to Slater’s articles by pointing out other trends that may have contributed to this squeamishness towards commitment, the point remains that our generation is fostering a culture where we demand everything as instantaneously as a Google search, relationships included.

While most high school students aren’t on dating sites (hopefully), that’s not to say that Facebook hasn’t naturally become its own pseudo-dating site.

It’s easier than ever to scan pages to find people who seem most compatible with you, whether it be for friendships or romantic relationships.

The problem is that when we open up too many options, we run the risk of picking friends scientifically, with precision, rather than trying to let relationships grow naturally.

Killing Curiosity

In July, Rick Ross and French Montana scored a summer hit with their song “Stay Schemin’,” but the real star of the show was a curious rap lyric by Montana: “fanute the coup to the ghost dog.”

The seemingly incomprehensible word “fanute” sparked a series of discussions, memes and a lengthy essay in The New York Times Magazine.

Eventually, Montana came out to say that it was actually “from the hoopty coupe to that Ghost, dog,” but at this point the damage had been done and the word “fanute” had become infamous.

The Times spun the story into a triumph—the idea that chaos, mystery and the evolution of language can still exist in this modern age.

“We can use the Internet to sniff out and suffocate every mystery from all four corners of the globe, from the grandest conspiracies to the pettiest dispute,” wrote columnist Will Staley. “Yet despite these attempts to control, categorize and define, there’s still somehow room for mondegreens like ‘fanute’ to break through and remind you why you like listening to rap.”

While the creation of the word may seem inconsequential, Staley makes a fair point about why the story is so amusing: We never see mysteries like this anymore.

We have devices in our pockets that can give us infinite knowledge and can explain away every question with a quick visit to Reddit, Yahoo Answers, or WikiAnswers. If those don’t work, maybe a quick Twitter post can get a knowledgeable friend to chip in.

This access to information is great—but at what cost?

Not sure how to interpret a dense passage of existential literature? Google it. Not sure whether it’s cool to like Vampire Weekend anymore? Google it. Not sure whether you should clean your room or watch TV? Just Google it.

When the obvious answer to every life question is “Google it,” we’re heading down a path where our screens have become magical crystal balls that hand over life’s answers on a silver plate.

Instead of liberating us with knowledge, we run this risk of letting the Internet essentially baby us and render us incapable of making the simplest decisions on our own without conferring with the entire Internet.

The Reddit Effect

And then there’s Reddit, the beloved “front-page of the Internet” and a perennial favorite of students across campus (much to the chagrin of network administrators looking to block the website).

Ups and downs, ups and downs.

That’s how Reddit works. Someone posts a photo, video, comment, question, anything and you vote it up or down.

This hyper-democratic process allows only the best content to reach the top of any given area of the site, from the front page to the comment sections.

But instead of increasing content quality, we instead see the creation of a hivemind that panders to the lowest common denominator.

Our senses of humor themselves have been changed—I have noticed a significant alteration in sense of humor amongst friends and acquaintances who spend significant amounts of time on sites like Reddit.

Humor itself is becoming regulated subconsciously. The hivemind decides what is funny, and once you start spending enough time online, it forces your sense of humor to adapt.

Conversations are becoming increasingly Reddit-like: nothing more than a string of punchlines with everyone trying to get in the last clever quip. It’s an oral reflection of the degradation of attention spans.

Tumblr is an interesting example. It’s supposed to be a blog for people to express themselves, something that some will guard dearly.

But at the end of the day, users are just reblogging someone else’s views, calling them theirs and joining cults of personality with thousands of reblogs per day.

What’s more, the idea that everyone can be a judge is something dangerous. By handing everyone the gavel, we see feeding frenzies where people’s reputations online (in the form of karma) are destroyed or created in seconds by the starving masses looking to be entertained.

You could call it The Reddit Effect, but you can just as easily see it in Tumblr (reblogs) and Facebook (likes).

With a click, we become the empowered arbiters of what is good.

The danger comes when we take this type of thinking into real life.

Don’t think it happens? Then why do we gawk at sites like FailBlog.org or watch the putrid likes of a cretin like Daniel Tosh?

Schadenfreude, the German word referring to pleasure derived from the pain of others, has become more than a guilty pleasure. It is now the code by which we live by.

But when everyone is a judge, is anyone safe from judgment?

Dancing in the dark

If you’ve made it this far, you probably think I’m some deranged Luddite blind to the values of the Internet.

Defenders of the Net will point to networking in the Middle East during the Arab Spring, the increased education one can obtain using a computer, the knowledge that you can chat with someone across the globe in seconds if you so please and the ability to network with those distant from you.

I think all those things are great, but how many of you are actually doing them?

As we move forward into the future, ask yourself to what ends you are using the Internet. Is it to promote the vanity and problems outlined above, or to truly better yourself and this world?

As an aspiring journalist, I recognize that inevitably social media will be a boon when it comes to the proliferation of useful information.

So, yes, I will probably be on social media sooner or later. But I’m making a vow to try my best to use it for good, to solve problems rather than simply point them out.

The late David Foster Wallace once eschewed the ironic detachment of the Internet Age by writing, “The next real literary ‘rebels’ in this country might well emerge as some weird bunch of anti-rebels, born oglers who dare somehow to back away from ironic watching, who have the childish gall actually to endorse and instantiate single-entendre principles.”

It’s time for us to decide: Do we want to be rebels or electric sheep?