By Ryan Loo ’21

THE ROUNDUP

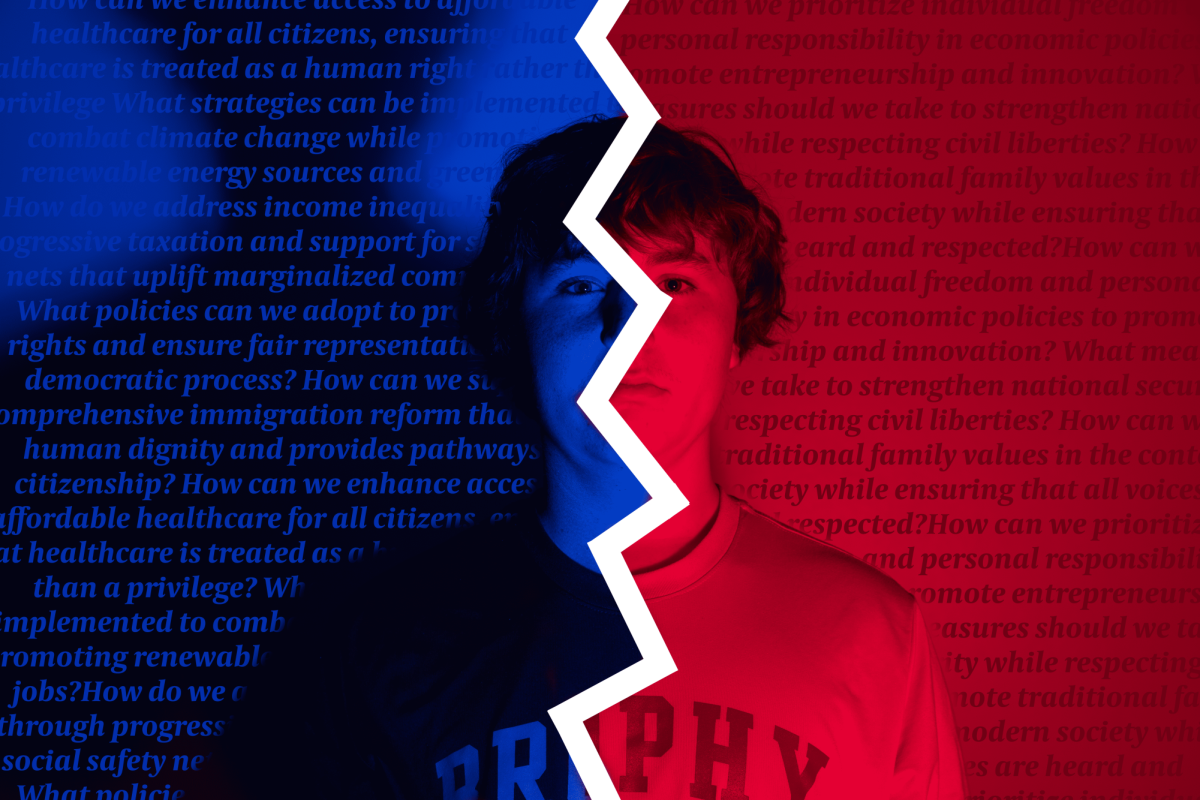

This past summer, the nation experienced bouts of civil unrest and protests sparked by the killing of George Floyd, one of the latest in a number of highly-publicized incidents of police brutality and killings of unarmed Black citizens.

Floyd’s death influenced pervasive shifts throughout America’s landscape. Corporations have issued statements. Politicians have taken sides. Even schools aren’t immune from the implications of this moment.

At Brophy, administrators have decided to wade into the debate by affirming Brophy’s commitment to social justice and unequivocally declaring anti-racism as a part of its school mission and long-term goals.

“This is the most important work we will be doing here,” said Brophy President Ms. Adria Renke, “There’s no doubt in my mind.”

Brophy admins see this action as an important alignment with the core tenets of the Jesuit mission to seek and promote social justice.

Indeed, it would be impossible to examine Brophy’s recent commitment to adopt an explicit school policy of anti-racism without taking a deeper look at the universal mission that underlies all Jesuit faith and education.

Faith, justice and solidarity with the poor and marginalized are central elements of the Jesuit mission.

This was explicitly stated at the Jesuits’ General Congregation 32 in 1975, where the Jesuits declared “the promotion of justice” to be a central part of the Society’s mission.

Brophy, as a Jesuit institution, has a commitment to promote those elements and that central mission. Programs such as the Kino Border Initiative are natural outgrowths of this commitment.

In response to the racial unrest displayed this summer, Brophy initiated a series of listening sessions with its Black families and students.

“We are going in depth with the [minority] experience to help educate us,” said Ms. Renke.

The purpose of these sessions was to listen and learn some of the realities facing these Brophy communities in order to see how Brophy as an institution could serve as agents of education and change.

Brophy has expressed that this is not a new mission, so much as an evolution of an existing one. Starting around 20 years ago, Brophy identified a need for increased diversity.

“At the beginning of the late 90s, our work really began,” said Brophy Principal Mr. Bob Ryan. “Now, it has evolved.”

What first began as an effort to increase the numbers of students from different communities and life experiences, gradually transitioned into a greater prioritization of more general tenets of equity and inclusion.

Now, Brophy’s diversity mission has evolved further. It is no longer enough to simply embrace diversity.

“The next step for us was to make a declarative statement that anti-racism is our goal,” Mr. Ryan said.

On July 17, Ms. Renke and Mr. Ryan disseminated an all-school email, announcing that “Brophy will deepen its commitment to anti-racism and affirm unequivocally that Black lives matter, not only in word but in policy and practice.”

I was very intentional in the letter about saying the words ‘Black lives matter’. That’s something we need to say as a school.

Mr. ryan

Brophy’s anti-racist declaration wasn’t just a statement on behalf of the Brophy community, but rather a personal commitment in which Mr. Ryan is personally invested.

“The statement we made in July as the leaders of the school was a statement that we made personally and on the behalf of the institution,” Mr. Ryan said. “This movement is really important to me and to Ms. Renke.”

The administration created a four-pronged approach to this institutional commitment, following the themes of ‘Representation,’ ‘Professional Development,’ ‘Curriculum’ and ‘Programming and Resources.’

Over the summer, to help enact this anti-racist commitment, Brophy staff compiled a thorough list of resources—articles, podcasts, videos, books, definitions—geared toward educating teachers on topics of race and increasing racial sensitivity both in and out of the classroom.

According to Mr. Ryan, teachers were partitioned into four different cohorts based on their current level of racial awareness and self-understanding as “racial people,” as determined through an independent inventory and survey.

The results of these actions have manifested somewhat subtly in the everyday curriculum and pedagogy found in the classrooms.

“I’ve seen a couple of instances where teachers have shared with me revisions they’ve made to their syllabus in those lines of work,” Mr. Ryan said, “or language that they are using in classes as a result of that work and part of our action plan.”

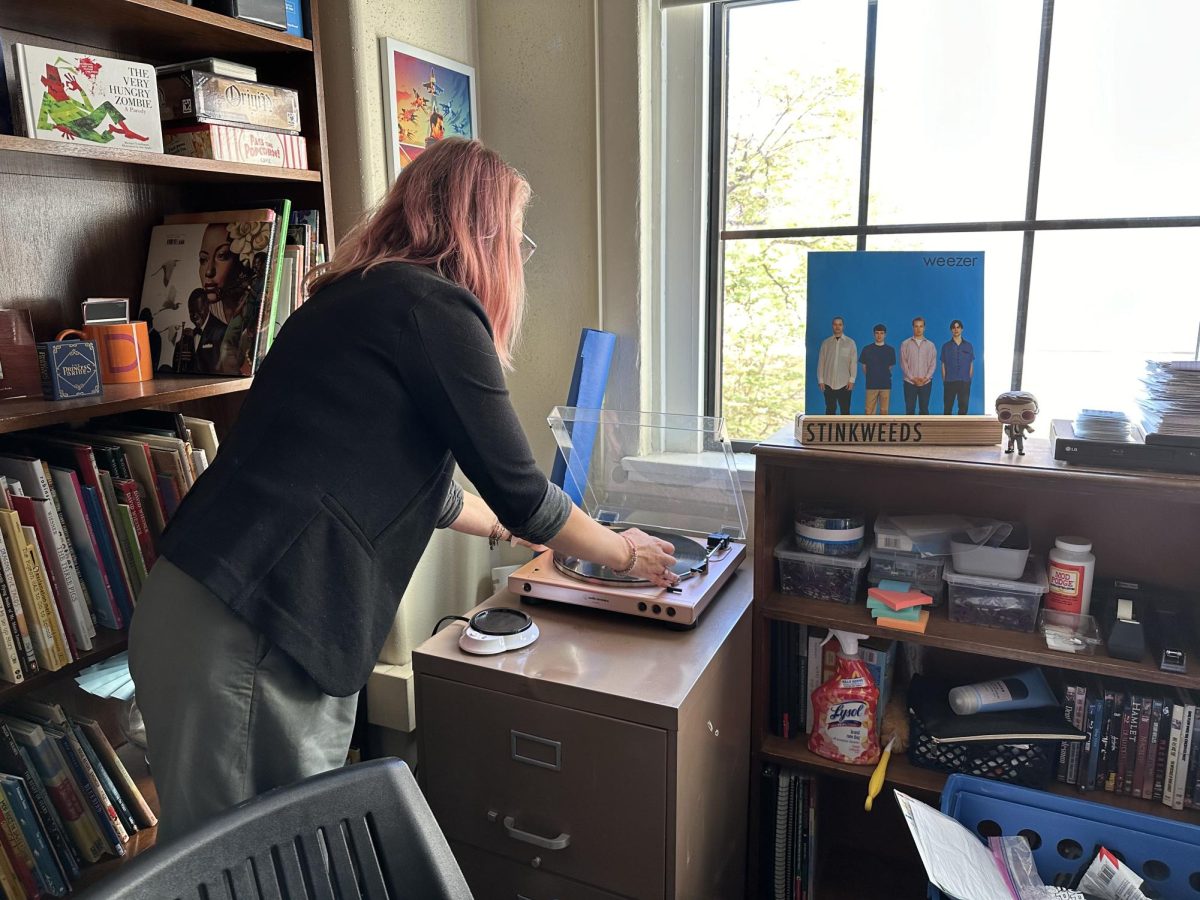

Mrs. Tanea Hibler, a Brophy AP Biology teacher, has taken full advantage of this opportunity to further explore topics of this nature, as they directly impact her and her livelihood.

“As the only Black female faculty member at Brophy, I don’t always feel acknowledged in my experience,” Mrs. Hibler said. “So when I read those books and articles, I felt relieved—I thought, ‘Oh that’s what I’ve been talking about, yeah you named it, that’s exactly it.’”

Furthermore, as the mother of two Black sons who might attend Brophy one day, the actions taken at Brophy now will personally impact her children in the future.

“I’m not doing this [anti-racist work] so that I can put this on my resume,” Mrs. Hibler said. “I’m working so that I can have an equitable experience as a science teacher and educator at my school and create a safe space for students who don’t feel like they necessarily have a safe or equitable space on campus.”

The collection of anti-racist resources that Brophy compiled and distributed to its staff this summer helped validate her experiences.

“It’s been really healing reading all of this anti-racism work and knowing that other teachers should also be reading it,” Mrs. Hibler said. “Maybe they are going to have a perspective that they haven’t had before.”

In addition to engaging with Brophy’s racial sensitivity training, Mrs. Hibler has been involved in educating herself and others on racial topics in a multitude of distinct ways.

“Personally, I’ve taken the time to do a lot of reading. If I don’t understand the history of this country and how racism operates, then I don’t think I can even begin to understand how to dismantle it,” Mrs. Hibler said.

Mrs. Hibler has striven to help educate others in her field of work regarding common misconceptions interlinking biology and race, and how to teach about such topics.

She will be hosting book club sessions with teachers and educational sessions with organizations such as STEMteachersPHX, American Modeling Teachers Association, iEMBER and the National Association of Biology Teachers.

Despite her involvement in the wide variety of aforementioned programs, Mrs. Hibler insists, “I’m not an expert in anything—I’m still learning. When I first came to Brophy I didn’t feel empowered to talk about these things in my class, so I understand that, as a teacher, I’ve made mistakes. I’m confronting my fears and my flaws and I’m trying to get better at my practice. It’s an ongoing process.”

Just as Mrs. Hibler is seeking to better herself through continuing education and growth, Brophy has expressed a similar desire.

Racial sensitivity training for teachers was Brophy’s initial step in its anti-racism commitment, however, Mr. Ryan doesn’t plan to stop there.

“It’s not like we’re going to say to someone who is in the nascent stages of their understanding of [racial topics] ‘Okay, now you’re the expert. Go figure it out,’” Mr. Ryan said, “Whether that means we hire consultants to come in and do ongoing training with folks—I’m totally open to doing that.”

Mr. Ryan is also excited by the prospect of having members of the Brophy community who are further along in their racial understandings to guide and direct others on their journeys, as well.

This process of racial instruction is ongoing. As long as Brophy stays open, this will always be a part of the mission.

“We’re going to have to keep revisiting things because we are always going to have new teachers,” Mrs. Hibler said. “We’re always going to have people that retire. Different people are at different points on their path in racial understanding, so the work can never end.”

“If there is an endpoint and we say that we’ve arrived, then it is not a commitment to me,” Mrs. Hibler continued. “Racism has been here for over 400 years. It’s not going to go away in 5 years at an historically predominantly white institution.”

Mr. Ryan is cognizant that he has many blindspots on the issues of racial work. However, this is not one of them.

“I have no illusion that this is all going to be better by May. This is work we are committed to for the long haul,” Mr Ryan said.

“Most people who are affiliated with Brophy have a four year membership card and then they move on. So their sense of our history is limited to only four years, but we’ve been a part of this work for a while,” Mr. Ryan said. “It’s not going anywhere.”

Furthermore, Brophy administrators are aware that people are watching for results and not just lip service.

“We want to be held accountable for the things we say we are going to do,” Mr. Ryan said.

“For example, in the area of representation, I’m well aware that the vast majority of our leadership team at the school is white—that’s a real concern and priority for us,” Mr. Ryan said.

However, Mr. Ryan understands that this process will be ongoing and he can’t promise immediate results.

“Some of these things are going to take time,” Mr. Ryan said, “but I’m aware that time can often be used as an excuse, so that’s why we—at some risk—actually put a date of November 1 on that letter.”

In this request to be held accountable, Ms. Renke and Mr. Ryan announced November 1 as the date by which they will publish specific details of Brophy’s anti-racist plan.

“The action plan we’re working on between now and November will focus on articulating … what the markers will be that we—and others—will be able to measure ourselves by to know whether or not we’ve actually made progress in the curricular area,” Mr. Ryan said.

Brophy has already begun charting tangible steps to take in order to concretely affirm its commitment to nurturing an anti-racist atmosphere both on, and off, campus.

However, big changes rarely come without some discomfort. While Brophy “didn’t get as much pushback as [they] expected or were prepared for,” Mr. Ryan stated that complaints were still filed.

Despite this, Mr. Ryan is unwavering in his position.

“I know [pushback] is out there and none of us should be surprised about it. We live in a racist society and we draw kids and parents from that society here,” Mr. Ryan said.

However, Brophy administrators believe it’s an integral part of the school’s Jesuit mission to help students leave their “echo chambers” and use the school’s platform to help form people as opposed to ostracizing and keeping them out.

We have the opportunity––every year with 400 kids––to change a culture. For the rest of my presidency, however long it is, this is my priority,”

Ms. renke

“For the sake of the world, [the students and families resistant to our anti-racism movement or any of this work] need to be here,” Mr. Ryan said.

Yet, Mr. Ryan recognizes the inherent privilege of this statement as a white, heterosexual male in a position of power.

“It’s easy for me to say as a white male, ‘Look, we’re going to have kids who make racial comments on campus, but it’s just going to happen because that’s the world they came from,’” Mr. Ryan said. “But I’m not the one who bears the pain of that. I try to continue to be mindful of the disproportionate burden that this work often places on people of color.”

However, even with uncertainties in mind, Mr. Ryan is confident in the direction in which Brophy is headed. “I feel really hopeful about the moment that we are in, in ways that I haven’t experienced in my time here. I think there seems to be a real desire across all constituents to move forward.”

And even if some members of the community aren’t aligned with the mission, “We get pushback all the time—that comes with the territory. It doesn’t for a second deter us,” Mr. Ryan said. “If anything, it gives us more reason to be bold.”