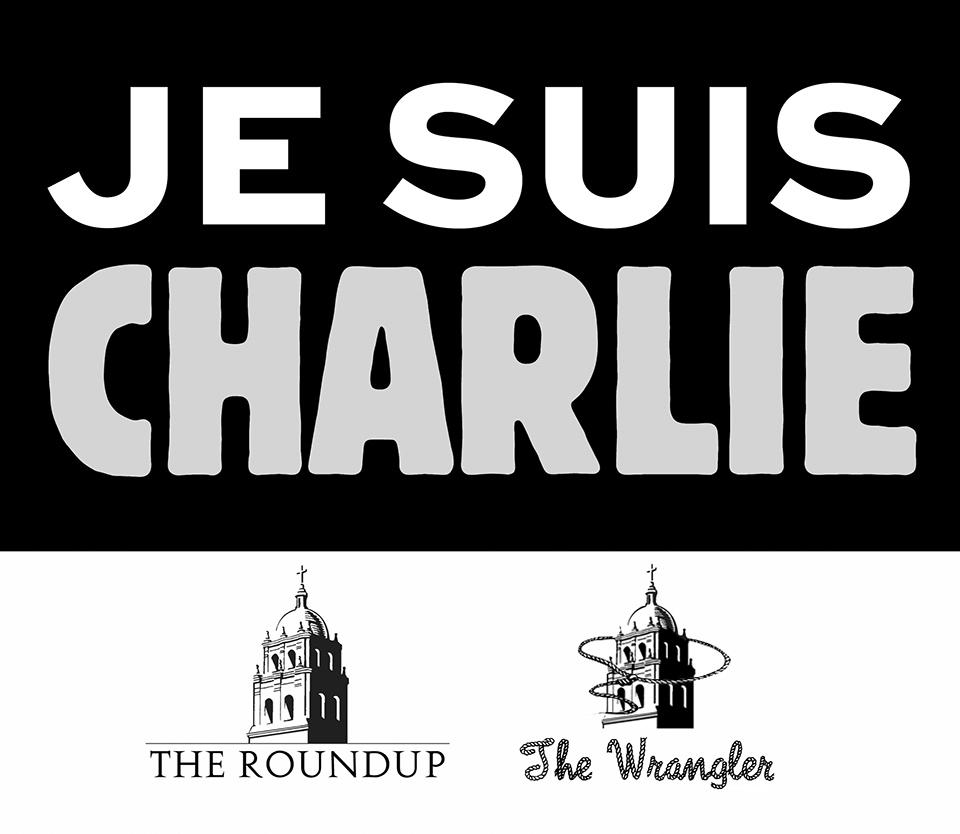

Media organizations across the world, including the National Scholastic Press Association that The Roundup is affiliated with, have tied their names to the Je Suis Charlie, or “I am Charlie,” movement. The Roundup and The Wrangler are lending their names to the cause, not necessarily in support of what Charlie Hebdo published, but in support of the right to publish freely without fear of violent retaliation.

The Issue: The recent Charlie Hebdo attack raises the question of whether there is a limit to free speech.

Our Stance: The press must be free, and no matter what the press produces there is no justification for violence. We must live in a society where words are fought with words.

Editor’s Note: Editors from The Roundup and The Wrangler, Brophy’s satire newspaper, worked together on this joint staff editorial in response to the recent attacks in France.

As writers and editors for The Wrangler and The Roundup over the past few years, we’ve been heavily exposed to the complexities of the free press, including satire.

Students on both staffs have devoted much time and energy to honing their craft, whether it is straight journalism with The Roundup or satire with The Wrangler. Students have also begun to probe the larger, more philosophical questions about the purpose of journalism and satire in our society.

Two extremists killed 12 editors and cartoonists Jan. 7 at the offices of French satirical newsmagazine Charlie Hebdo.

Terrorists used Charlie Hebdo’s offensive caricatures as justification for the shooting that sent France into a nationwide terror lockdown and led the rest of the world to consider the true value of a free press.

Images of the peace protests in Paris showed activists holding pens in the air, signifying their defiance and the value of pens over guns.

This is an image we should all consider.

To be clear, this is not about the content that Charlie Hebdo published.

Rather, this is about the necessary right of a free press to publish without fear of being killed.

Because of the freedom of the press, it is acceptable to produce satirical images of the Muslim faith like Charlie Hebdo did. A responsible press should always consider its intentions before publishing any work, but they must have the right to publish whether the content is considered offensive or not.

The press must be free in order to keep a society honest and informed in order to change what the public does not agree with.

Although each country has its own limits on free printing rights, a free press is absolutely vital to a fair and accountable society.

The attacks in Paris on the Charlie Hebdo staff marked a horrendous, even abominable act of violence. This is obvious and undeniable.

Any person equipped with basic human decency and a commitment to freedom can, and should, denounce these events.

What compels us, however, are the more difficult questions posed about the purpose of satire and its right to offend.

What are the limits of satire?

Does satire have a right, perhaps even a duty, to offend?

Satire in France originally took prominence during the French Revolution, when the French people rose up to fundamentally alter the structure of their society.

This type of political humor focused foremost on the satire of establishment, no matter the party or ideology that held power.

Slightly different from the highly ironic and witty mainstream American satire that inspired The Wrangler, Charlie Hebdo continued to uphold this anti-establishment standard, extending its excoriating humor to all political parties, races, and religions.

One could make the very convincing argument that Charlie Hebdo’s Islamic caricatures were simply an extension of their commitment to lampooning all facets and groups of French society.

However, what makes the situation more complicated is the fact that Muslim-French relations, specifically, have been especially tense over the past few years.

In effect, one could also agree that Charlie Hebdo’s Islam-targeted satire was different than its past publications, given the strained nature of Muslim-French relations in Paris.

We still struggle with these questions about the role of satire and its right to offend, but ultimately whether we agree with the material Charlie Hebdo published is irrelevant.

What we are sure of is this: We should have the right to publish, even if it offends.

The Wrangler experienced this dichotomy firsthand last March, when its staff produced its edition on the Summit: Beyond Colorblind.

As the staff moved through the initial stages of production on this issue that covered a potentially controversial topic, it became clear that there was a choice: either use satire to attack stereotypes and skewer injustices, or simply devolve into the type of stereotype-driven, racially-insensitive comedy that has littered so much of our culture.

In this case the decision was easy for us, but Charlie Hebdo should be free to make their own decisions without the consequence of violence.

In a democratic society satire cannot be censored by authority. And, while satirists themselves should be self-policing in their provocation, it is ultimately the responsibility of the citizens to discern the difference between good and bad satire.

In a free-thinking society, it is the prerogative of the citizens to be active and critical consumers.

We can not only make our voices heard through discussion and publication, but also through the consumption choices that we make: good satire will be bought and cherished, while perceived crass and unnecessarily offensive satire is not.

Though we have not completely reconciled all of our thoughts between satire and offense, the Charlie Hebdo slaughter has reminded us of an important lesson:

Regardless of the offense, we must live in a society where words are fought with words.

While some might argue that Charlie Hebdo’s material was offensive—and do so convincingly—the response of violence is unjustifiable.

Staff editorial by Garrison Murphy ’15, Austin Norville ’15 & Anand Swaminathan ’15

THE ROUNDUP & THE WRANGLER

Staff editorials represent the view of The Roundup. Share your thoughts by e-mailing roundup@brophyprep.org or leave comments online at roundup.brophyprep.org.