Photo by Jackson Moran ’21 | Diego Avocado-Garcia ’21 checks his blood sugar during lunch.

By Jackson Moran ’21

THE ROUNDUP

Brophy has many students on campus whose diabetes permeates most aspects of their routine.

Diabetes affects over 200,000 people under 20-years-old in the United States, according to Beyond Type 1, a nonprofit that educated people on Type 1 diabetes.

Diego Acevedo-Garcia ’21 is one of these diabetic students.

Born in Chihuahua, Mexico, Acevedo said that he developed Type 1 diabetes when he was very young.

“At that time, they [medical personnel in Mexico] were not used to kids my age having the disease,” he said.

His condition escalated from there, when he started showing dangerous symptoms.

“I started vomiting, and one day it got to the point where I fell into a two-week coma,” Acevedo-Garcia said.

It was at this point that he and his family found out that he had Type 1 diabetes, which is very rare for children of that age.

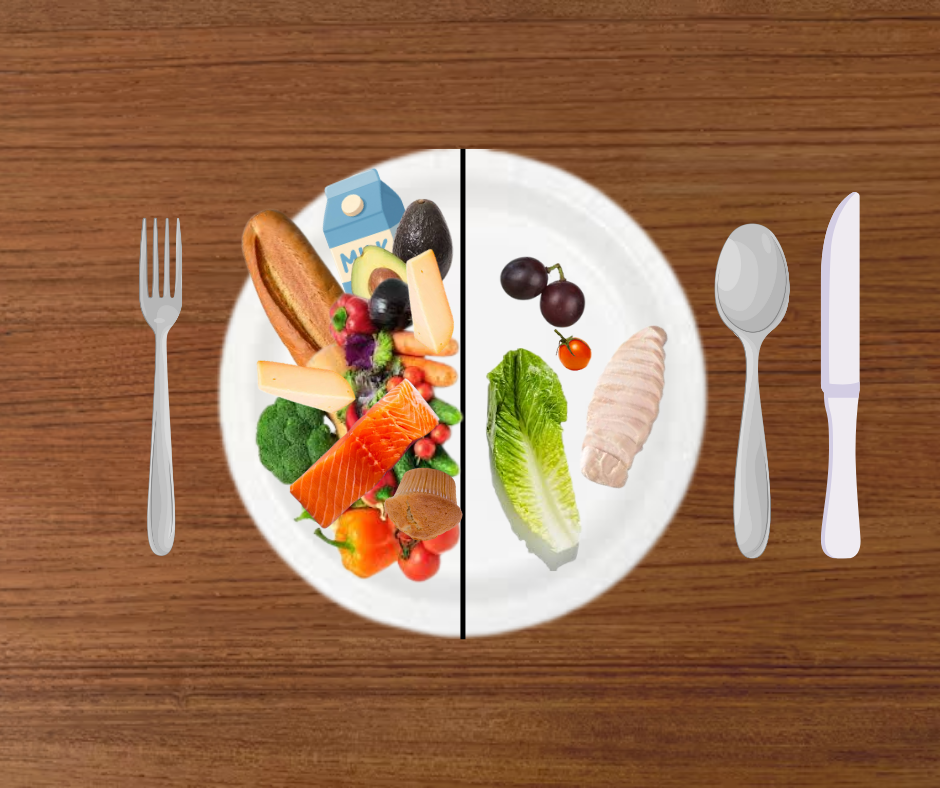

Acevedo-Garcia said that there are really no limitations placed on him because of his diabetes, just precautions that he must take.

“I can eat and do pretty much anything, I just have to take certain measures to control my diabetes,” he said.

This is a common experience shared between other students who have Type 1 diabetes.

Nick Hahne ‘22 was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes when he was 10 years old.

For Hahne, having high blood sugar can lead to irritability or even, in extreme cases, a coma.

“Every time I take in sugar, I have to take a shot of insulin as a reaction to balance my body,” Hahne said.

This is a necessary task for diabetics, as the pancreas is not able to release the insulin needed to process high blood glucose levels.

Testing blood glucose levels is made easier by machines, but it is still a tedious task that is done many times a day.

“Every single meal, it’s checking my blood sugar and taking my insulin. I check my blood sugar at school during break and lunch and even during some classes,” said Kolbe Bayless ’20.

Bayless was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes during his sophomore year.

He also said that that may seem like a lot to do, but that after a while it just becomes regular routine.

For example, Acevedo-Garcia checks his blood sugar around six times a day.

Acevedo-Garcia and Bayless both use insulin pumps, where carbohydrate amounts are input, and the pump then calculates how much insulin to administer.

“It makes things a lot easier…it’s just connected to me so I do not have to give myself any shots,” Acevedo-Garcia said.

Managing diabetes in the classroom is very important, as low blood sugar levels can alter your mental state.

“Having low blood sugar can really affect your mental processes and how you think,” Bayless said.

He also had to excuse himself from a test due to his blood sugar affecting his ability to accurately and effectively complete the assessment.

Hahne also had a similar experience one day during his fourth period class.

“My blood sugar fell way below where it should have been, and as a result I had to go to the dean’s office and take some quick sugars along a couple of juice boxes in order to onset my blood sugar,” Hahne said.

Diabetes also has to be managed by athletes, as low blood sugar levels during physical activity can be very dangerous.

“One restriction that I deal with a lot is that I’m a competitive swimmer, so often I will have to get out of the pool for blood sugar reasons,” Bayless said.

Swimming with a low blood sugar is very dangerous, as it can cause you to lose consciousness in the pool.

“For practices, I try and shoot for a blood sugar around 200, and if it’s too far below that it becomes unsafe for me to be in the pool,” he said.

Practice levels, however, do differ from race levels, which Bayless said is often vital to his performance.

Consistency and vigilance is key when it comes to managing blood sugar while competing on sports.

Acevedo-Garcia also competes as a cross country runner, and has learned to manage his blood sugar while running.

“After some talks with my endocrinologist and after having experience in the sport while dealing with diabetes, I got to a point where I know what to do if anything bad happens,” Acevedo-Garcia said.

His running is normally not affected by diabetes, and he does not let it slow him down.

Hahne plays soccer, where he said that he must also make sure that he has correct blood sugar levels, and must maintain them throughout the game.

“If I am exercising more than I expected, and my blood sugar falls, then I have to be removed from the game,” Hahne said.

He also added that the soccer coaching staff easily accommodates for his condition, and that he need only ask for a sub, and the coaches will provide him with convalescence time to manage his blood sugar.