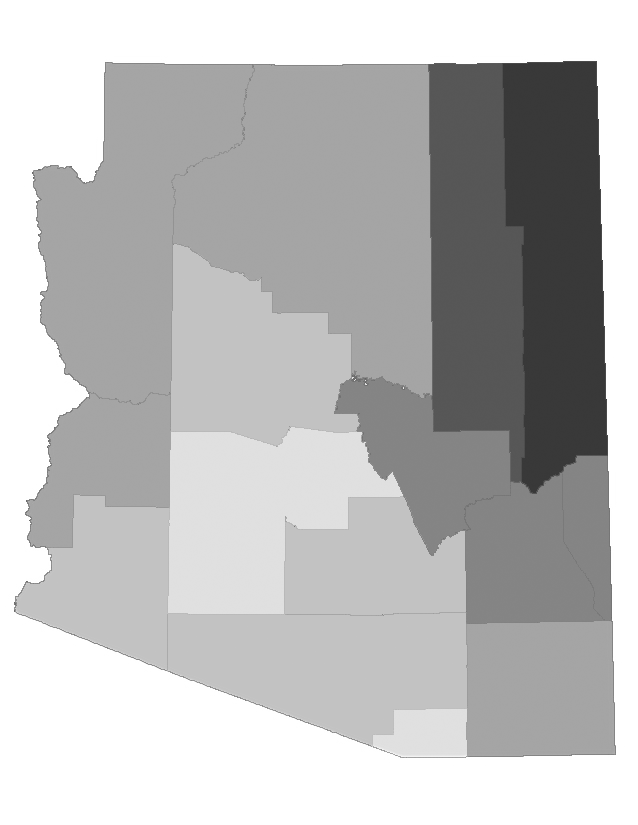

Data collected and illustrated by Jacob Cross Mayhew ’20 and Nick Pecora ’21

By Harrison Cohen ’20 and Jacob Cross-Mayhew ’20

THE ROUNDUP

A recent report by the United States Water Alliance and human rights nonprofit, Dig Deep, stated that race is the strongest determinant in access to clean water in the U.S.

“More than two million Americans live without running water and basic indoor plumbing, and many more without sanitation,” said the National Action Plan, titled “Closing the Water Access Gap in the United States.”

The report found that clean, running water is “out of reach for some of the most vulnerable people in the United States: communities of color, lower-income people in rural areas, and tribal communities, among others.”

These problems stem from many of the water crises across the U.S., most of which occur in disproportionately poor areas.

In 2014 in Flint, Michigan, a pipeline was installed which contaminated the community’s water with lead, resulting in dangerous health concerns in those who consumed it. The water crisis in Flint caused a lack of water supply for the city for years, and there is still concern that the water is still unclean.

“In the case of Flint, Michigan, it was definitely a more impoverished black community in which the water infrastructure hadn’t been updated in decades, which resulted in a massive water crisis,” said Isaac Peters ’20, the co-founder and co-president of Brophy’s H2O club. “There were massive amounts of lead poisoning in the water, and they couldn’t get the water system clean for a few months, which caused major water shortages in the area.”

Outside of the U.S., a similar need for access to water is dire, with 790 million people lacking an improved water supply, according to the Center for Disease Control.

Peters’ H2O Club is focused on educating the Brophy student and faculty body about the issues of water throughout both the country and the world. Peters has learned that more water issues persist in developing countries than in developed ones, like the U.S.

“Most of it occurs in underdeveloped countries with poor infrastructure where the governments don’t pay a whole bunch of attention to people’s needs … which leads to many waterborne illnesses and deaths in those countries,” Peters said.

Mr. Patrick Kolb, moderator of the H2O Club and Environmental Science teacher, also attributes much of the worldwide water crisis to a lack of governmental focus on the issue.

“The governments who are charged with keeping the water clean don’t always do it,” Mr. Kolb said. “There’s clean water caused by biological contamination, industrial contamination, and that really applies everywhere. I mean, in Michigan we had a water crisis in this country recently.”

“Some countries just don’t prioritize clean water for consumption,” Mr. Kolb said. ”They might prioritize clean water for manufacturing instead because the government gets more immediate return on their investment.”

In addition to the issue of race in the lack of access to clean water, financial inequalities are another large factor.

“There are issues with inequality. Polluted land has polluted water. Polluted land is cheaper. People with less financial means are more likely to live on said land,” Mr. Kolb said.

“Well, in this country we’ve had links between financial means and race. And, if you draw a parallel between access to clean resources and financial means,” Mr. Kolb said.

“You are also going to draw the same conclusion that different races have different access to clean water,” Mr. Kolb continued.

Unequal access to clean water is directly correlated to racial inequality and inequity. Throughout history, clean water has not been for all. “Whites Only” signs on water fountains were present across America less than sixty years ago.

Water inequality particularly affects low-income communities. A 2018 report by the University of California Davis Center for Regional Change reports that an estimated 350,000 people in the San Joaquin Valley do not have clean drinking water. Additionally, a report by the U.S. Water Alliance estimates that nearly two million Americans do not have access to running water in their homes.

Mr. Kolb described the negative effects of lack of clean water, and said, “If you have a group of people that don’t have access to clean water, they might not have the same health and they may not have the same access to education, for example. You don’t have the same access to education, you may have less opportunities.”

“Well, in this country we’ve had links between financial means and race. And, if you draw a parallel between access to clean resources and financial means … you are also going to draw the same conclusion that different races have different access to clean water,” Mr. Kolb said.

The interim-director of the Office of Equity and Inclusion, Mr. Marcos Gonzales, shared a similar sentiment, saying, “Poor communities, which unfortunately tend to be communities of color, are often most affected by lack of access to clean water.”

Mr. Gonzales believes that the key relationship between equity and water is access to clean water.

“Unequal access can be here in Phoenix or a national scale, with examples like the Dakota Access Pipeline and access to clean water by native peoples and the situation in Flint, Michigan highly impacting the African-American community there.”

Mr. Gonzales believes that “awareness is key. The more we know who is impacted and our relationship with water and the systems that give access to water, we might gain a desire to change the simple ways we relate to water and those who don’t have water.”