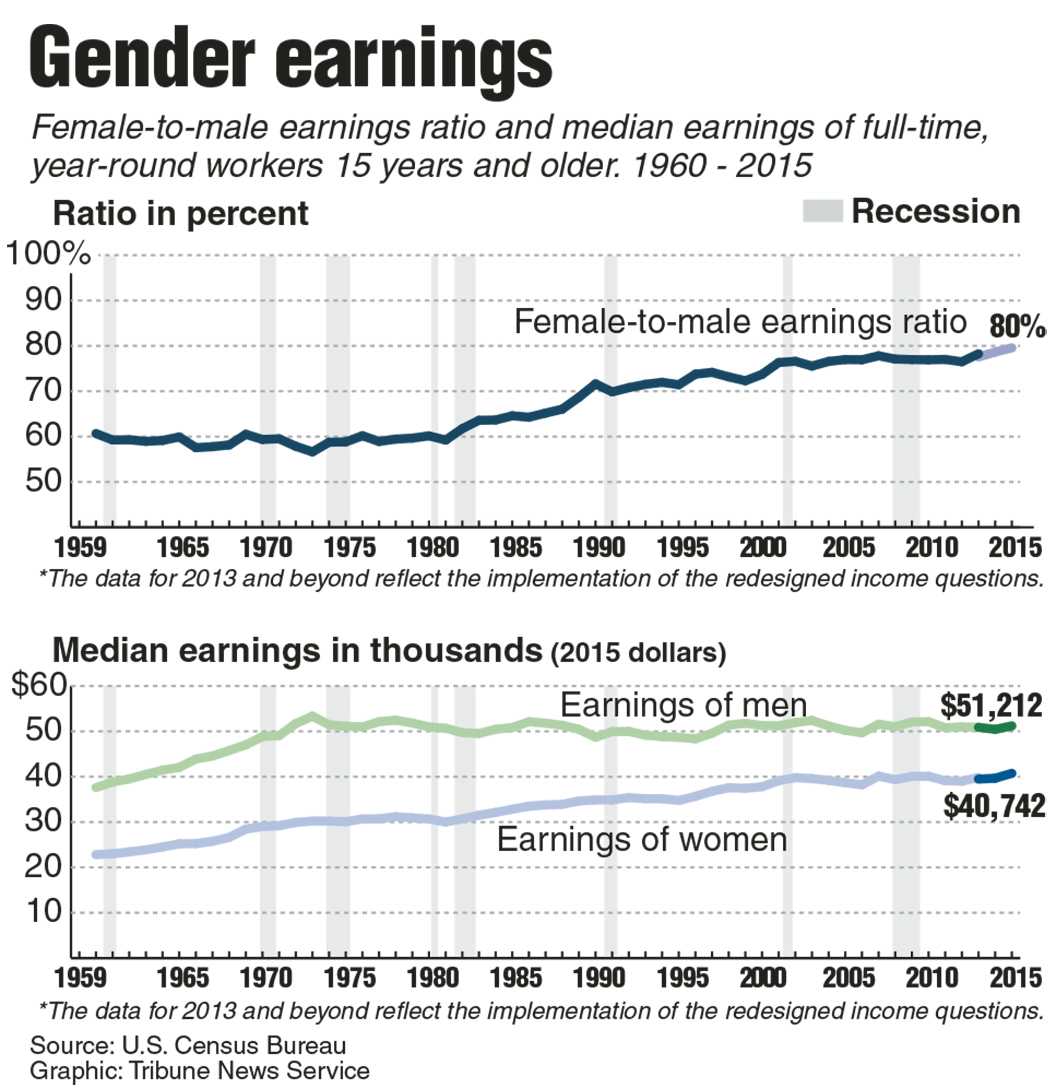

Chart showing female to male earnings from full-time, year-round workers. TNS 2016

By Jack Cahill ’17

THE ROUNDUP

People of all political persuasions can likely agree that the wage gap, the difference in median pay between men and women, is ultimately a negative thing.

The American Association of University Women released a detailed study on the facts of the wage gap.

In 2015, women working full time were paid just 80 percent of what men were paid. At this rate, the gap won’t be closed until 2152, because the gap has hardly made any signs of improvement in the last several decades.

There are myriad explanations as to why this is the case, and while some are purely circumstantial, other explanations reflect problems within businesses and wider society.

First, we need to be fair.

According to the US Department of Labor, the pay gap on paper is 20 percent, the real number is around 8 percent when variables such as children and hours worked are taken into account.

Eight percent, however, is still a gap, and not an inconsequential one.

For instance, a man who makes $100,000 will see his female colleague making $92,000 for the same exact job.

So while partisan alarmism on the issue is unfounded, concern is reasonable.

A Harvard study conducted by economists found that evaluators and employers are more likely to hire men over equally qualified women.

Similar studies, such as one conducted by David Neumark of the University of California found that a qualified woman is 35 percent less likely to receive a promotion or pay raise than an equally qualified male counterpart.

Similar studies find direct evidence of discrimination, finding that more jobs went to women when the applicant’s sex was unknown during the hiring process.

We can all agree that direct evidence of discrimination is a bad thing, but people tend to disagree on what to do about it.

A kneejerk reaction might be to advocate for the government to make it illegal for companies to discriminate based on sex. That’s a sound idea, but the government did just that with the Equal Pay Act of 1963.

In reality, two things need to happen.

For one, the companies or the government itself should implement flexible and reasonable policies such as paid family leave and supported childcare that enable mothers to be both moms and workers.

Women without children make 94 percent of what men do, whereas women with children make 78 percent of what men do. With balanced policies aimed toward helping mothers work, we can begin to close the gap.

Secondly, we need a large scale change in attitude as a culture. While claims of widespread discrimination are often exaggerated and made political, it is true that many businesses often prefer men over equally qualified women.

Frankly, it is unfeasible to make that illegal, because we have already tried and cracking down on this would ultimately infringe on the rights of a private business.

This is why we need to promote and cultivate a culture that promotes respect toward women in the workplace, and a culture that promotes a view that women and mothers are just as capable as men.

As the next generation of male workers, it is our responsibility to make this our problem, rather than something we can take advantage of.

We need to start a dialogue on promoting a culture that values women and mothers in the workplace just as much as single men.

The wage gap is often politicized and perhaps even over or under exaggerated by different groups, but it exists. We can take practical steps to reduce the gap, even if we may never fully close it.